One year on: Russia’s COVID-19 crisis

After a decade of economic stagnation, oil price instability, military conflicts in Ukraine and Syria, and international sanctions and counter-sanctions, 2020 was to be a year of revival for President Putin and Russia. A constitutional referendum in April; national V-E Day celebrations in May; and the acceleration of the $362bn national investment plan to renew Russia’s public infrastructure, lift living standards, drive up economic growth and, of course, revive Putin’s flagging approval ratings. Unfortunately for Putin, these plans were interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Russia was quick to respond to the emergence of COVID-19 by closing the border with China in late January and introducing controls on arrivals from South Korea and Italy. Sadly, it was far slower to appreciate domestically spread infection, suggesting instead that the threat was greatly exaggerated. Notwithstanding reports of what appeared to be COVID-19 cases in Komi, Bashkortastan and Dagestan, the first two official cases were registered on 15 February 2020, the first domestically transmitted infections were confirmed exactly one month later, and the first death on 19 March.

During this period, Putin’s response appeared somewhat erratic. As late as 17 March, he reported that the COVID-19 situation in Russia was “under control” and that Russia had been able to avoid a mass outbreak. It was only on 24 March, 38 days after the first officially registered cases – and two days after the Moscow Mayor, Sergei Sobyanin, had introduced restrictive measures in Moscow – that Putin’s tone began to change, following a well-publicised visit to a Moscow hospital with Sobyanin.

The following day, Putin, addressing the nation on COVID-19 for the first time, made clear that Russia could not isolate itself from the global threat of the pandemic. He announced a non-working week with full salary, postponed the constitutional vote, but did not announce any overarching restrictive measures. The non-working period was soon extended through to the May holidays, with a promise (backed only by limited financial aid) of full pay for all workers.

Putin then retreated to his country residence, regional governors were endowed with additional authorities to manage the crisis locally, the federal government was effectively bypassed, and Moscow Mayor Sobyanin became the public face of government efforts to control the spread of the disease. During this period, the spread of COVID-19 was rapid. Within a few weeks of these initial policy actions there were over 60,000 recorded cases and over 500 officially recorded deaths and, by mid-May, Russia’s rate of new infections – at over 10,000 per day – was second only to the US. By 1 June, there were over 400,000 officially recorded cases.

This was Russia’s wave one (Figure 1). The pandemic had reached Russia later than in other European countries, but Russian caseloads (unlike in e.g., Ukraine, where the ‘lockdown’ policies were stricter) soon matched those of the worst performing countries (e.g., US, UK, France, Italy). Two additional differences stand out: unlike in most European countries, the decline in case numbers from the peak of wave 1 was much shallower in Russia (Figure 1); and the number of official deaths attributed to COVID-19 was substantially lower than elsewhere (Figure 2).

Indeed, despite having the world’s second highest number of confirmed cases, the case-fatality rate stood at approximately 1%, compared to 6% for the US, 13% for Italy and 4% for Germany. Naturally, questions were asked and the explanations, rather than assuaging sceptics, simply added to the growing interest in ‘excess mortality’ as a preferred indicator of the health consequences of COVID-19.

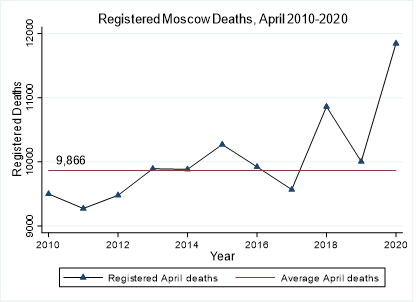

Under pressure, Moscow City Government then rapidly published data on its total registered deaths for April, showing a large spike in mortality occurring in April 2020 (Figure 3) with mortality 20% above the 10-year average, well in excess of the two flu epidemics of 2015 and 2018 and significantly beyond the official COVID death rates for Moscow. Even so, this level of excess mortality was still below that seen in New York, London, Paris, and Madrid.

Once the six-week period of “non-work” had ended on 11 May, there were no further gestures towards the national “lockdowns” seen elsewhere. Instead, Putin encouraged the country to re-open and to stay open, blaming regional governors for deviations from this. Moscow, with its vast municipal resources, was able to maintain restrictions – introducing population tracking with QR codes, CCTV surveillance of vehicle movements, ensuring the closure of shops, restaurants, and other facilities, while also constructing new medical facilities (e.g., Kommunarka). However, elsewhere there was little resource for enforcing or incentivising restraint and Russians had little choice but to continue working even when localities encouraged caution. Beyond Moscow therefore, there was nothing approaching a “lockdown” to protect the population from COVID-19.

Accordingly, while numbers fell sharply during the summer period across Europe, in Russia the decline in caseload was more marginal, and before summer’s end, the second wave of COVID-19 had taken hold. By October, cases were already beyond that of the first peak, with new daily infections approaching 20,000. Even as President Putin was insisting that there would be no ‘lockdown’, his Deputy Prime Minister – Tatiana Golikova – was reporting that hospital bed capacity was already over 90% in 16 Russian regions; proof that already underfinanced regional health care systems were at breaking point, before winter had even begun. Inevitably, as the reality of the second wave dawned, some restrictions were reintroduced, with gloves and masks mandated in Moscow and some home schooling and working reintroduced, but there was no systematic lockdown and no official recognition of a second wave or a need to react to it.

And so, while President Putin spent his end of year press conference drawing attention to Russia’s relatively successful economic journey through the 2020 pandemic, Rosstat – the official statistics agency for Russia – began to convey a much bleaker story about the real human toll of Russia’s COVID-19 experience. Figure 4 below is stark, showing that 323,802 extra deaths occurred in 2020 compared to 2019 – an increase of 18%. This falls to 15% if we compare 2020 with a five-year average but rises to 25% if we compare the last 8 months of 2020 with the corresponding months of 2019. Whichever metric we choose, Russia appears either at the top, or near the top of the global list of excess mortality figures and, as elsewhere, a large proportion of these deaths are the cost of the policy choices made.

Few governments can look their populations in the eye and claim to have handled the pandemic successfully. Yet, from the late recognition of the internal threat, to the half-hearted initial lockdown, to the refusal to protect the health of the population as the second wave approached, Russia’s policy makers have prioritised economic freedoms to such an extent that the poorly funded health systems across Russia have been unable to prevent a catastrophic spike in mortality that will have lasting consequences for public health, but also for the economy.

Professor Christopher J Gerry

Director of Russian and East European Studies, University of Oxford.

April 2021